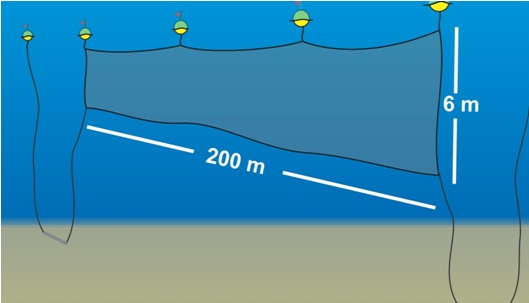

A shark net is a submerged net placed around beaches to reduce shark attacks on swimmers. Shark nets do not offer complete protection, but work on the principle of "fewer sharks, fewer attacks". They reduce occurrence via shark mortality. Reducing the local shark populations is believed to reduce the chance of an attack. The large mesh size of the nets is designed specifically to capture sharks and prevent their escape until eventually, they die. Due to boating activity, the nets also float 4m or more below the surface and do not connect with the shoreline thus allowing sharks the opportunity to swim over, under and around nets.

Shark Net Bycatch

With the use of shark nets there is also the high incidence of bycatch, including threatened and endangered species like sea turtles, dugongs, dolphins and whales. We encourage the use of alternative non-lethal approaches, such as surf lifesaving, public education on shark behaviour, radio signals, sonar technology and possibly electric nets.

Drum Lines

Like shark nets, a drum line is a device used to reduce the amount of shark attacks at popular beaches by capturing sharks on the drum line's hook. While most drum lines are used in addition to shark nets, it has been suggested that drum lines are actually more effective at catching the three more deadly sharks (Great White, Tiger and Bulls). As a result, drum lines are viewed, by some people, as an alternative to shark nets as they consist of baited hooks aimed at catching only large sharks (though turtles are also hooked and subsequently killed).

Shark Nets: The Australian Perspective

(Written by

Christopher Neff for

www.theconversation.edu.au)

How Did All This

Netting Get Started?

Along 51 beaches and 250 kilometers of New South Wales coastline, beach nets line the surf. Beach nets were approved in 1935, but only as a two-year experiment. However, by 1937 there had been no shark bites and no Government funding. The reason the state financed netting that year was NSW’s imminent 150th Anniversary: state politicians were worried there would be a shark attack during the celebration.

During the Second World War, beach nets were removed from ocean beaches so fisheries ships could be used by the Americans. For three years, between 1943 and 1946, there were no fatal shark bites at these un-netted beaches. At the end of the war, New South Wales Premier William McKell announced in the Sydney Morning Herald that beach nets were “quite valueless”, noting that “since meshing ceased in January 1943, there had been no shark fatality on our beaches.” However, instead of abandoning shark nets, the Premier announced plans to use them in combination with experimental shark repellents because: “if meshing alone were used, I fear it would prove to be of little value. Worse, it would possibly lull the public into a sense of false security, leading to diminished watchfulness and possibly to tragedy.” With no shark bites and little threat in these locations, the nets were put back and expanded to the Illawarra and Hunter under this new plan of action. Most recently, beach nets were re-endorsed in a Department of Primary Industries Report in 2009.

What really stops

shark fatalities?

The DPI’s 2009 review provided a contemporary view of shark nets. Then Environment Minister Ian Macdonald called the nets “highly successful.” Yet the report of shark bite incidents from 1937-2008 showed that of the 38 shark attacks recorded in the state, 24 of them (63%) took place at netted beaches, with 14 injuries. The Minister and Department correctly point out that there has been only one fatality at a netted beach (1951) under this program. But attributing low fatality rates to beach nets is questionable. Internationally, fatality rates from shark bites have declined dramatically for all shark control methods, including doing nothing.

Irish trauma researcher David Caldicott published a study in 2001 showing the survival rate for shark bites is 80%, due to better on-scene treatment and antibiotics. The leading reason for fatalities was blood loss. (In fact, when Marcia Hathaway’s tragedy took place in Sydney Harbour in 1963 the ambulance broke down.)

The Government’s shark bite data suggest a number of possibilities. It could be that the nets are vitally needed since there were clearly sharks in those regions. But the 63% failure rate raises fundamental questions about their effectiveness.

To be fair, beach nets aren’t just installed to prevent sharks and people interacting. Nets were originally used, in 1935, to cull populations so there would be fewer sharks and therefore fewer shark alarms. In the 2009 DPI report, it was argued that, although culling is indiscriminate, the goal is to kill larger sharks to reduce the risk of a fatal shark bite incident. And killing sharks (and other marine species) is one thing nets do very well.

Is There an

Alternative?

At this point, I think it is important to recap the central elements.

-

First, shark nets were nearly left out of the report in 1935 and were only funded in 1937 as a precaution ahead of the state’s anniversary.

-

Second, there were no fatal shark bite incidents when the nets were removed for three years.

-

And third, nets have been deemed very successful even though 63% of shark attacks at ocean beaches in New South Wales have occurred at netted beaches.

In all, I suggest that at key points in the history of shark nets this has proven itself to be a story about people and politics rather than shark behaviour. So what do we do instead? It is not a simple matter.

Internationally, shark nets have been labelled a “key threatening process“ for killing endangered species. In 2011, killing endangered species to boost public confidence or to show government action is not workable. It is a disservice to the public. To restore an objective critique of this emotive issue we need a workable alternative.

Time for

Australia to Catch Up

If killing sharks is taken off the table, then other innovative beach safety options are possible. In Cape Town, Florida, New Zealand and Hawaii, lethal shark control methods have been replaced by more modern beach safety tactics.

These tactics include greater uses of signs and flags to educate the public about marine hazards and using tracking devices on sharks to determine seasonal movements. This has begun in Sydney Harbour, but could be expanded. A fundamental question is whether shark safety should be based on decisions that governments make, with policies determining our personal level of risk in the water, or whether the public should be empowered and educated to make its own determinations?

This analysis is not intended to minimize the terrible consequences from shark bite incidents. Sharks do bite people and public safety measures should be taken.

It is not clear; however, if the status quo is actually working.

The truth about shark nets is also about “truth in government”. Government action and the public’s role cannot be obscured by the dreaded nature of these events. The time has come for a new public dialogue about public education and beach safety regarding sharks, not simply because beach nets harm the environment, or because there are questions about whether they work, but because these 70-year-old tactics mean Australia is being left behind.